The norm with good reason

Milk is our first source of nutrition. We would never survive infancy without it. Woe betide anyone who interferes with its supply in the first months of life – we will wail and cry until our craving is met. Isn’t it strange then that a majority of people suffer from lactose intolerance?

Lactose intolerance is indeed the norm for most people. And for good reason – our bodies lose the ability to break down lactose or to produce the digestive enzyme lactase as we grow older, although this process actually starts in early childhood. After weaning, the body has no need to utilise lactose.

Lactose intolerance and its geographical hot spots

Lactase is an enzyme that occurs in our intestines and ensures that the milk sugar or lactose in dairy products can be broken down into glucose and galactose. Lactose intolerance is not an allergic reaction – it's the most frequent food intolerance around the world. The symptoms of lactose intolerance usually become evident as gastrointestinal complaints such as abdominal pain, diarrhoea and flatulence.

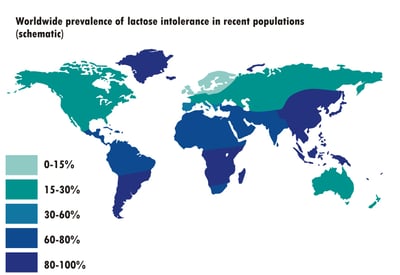

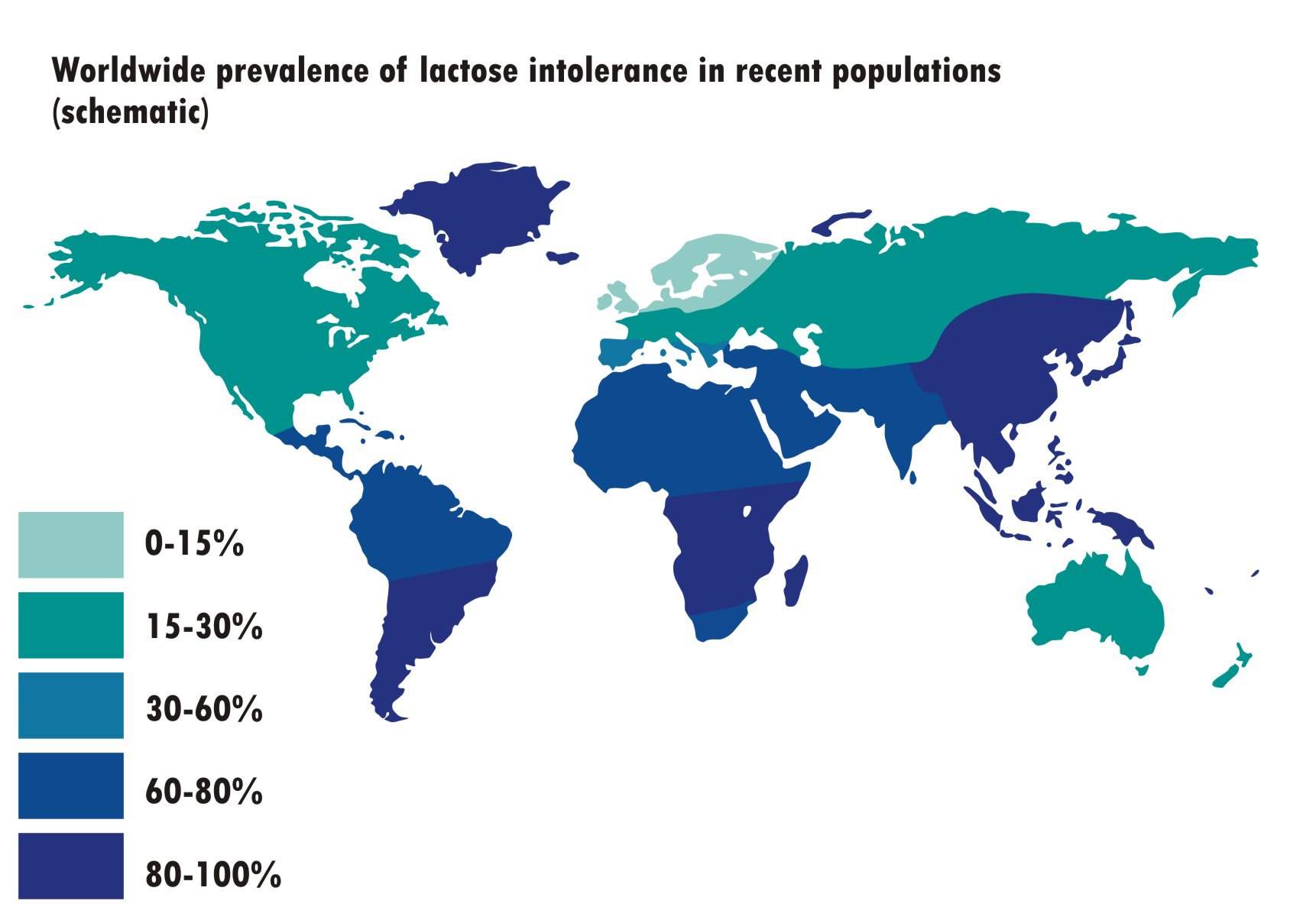

The body’s ability to tolerate lactose, including in adult life, has developed very differently in various parts of the world. The geographical differences are striking.

Lactose intolerance is mainly prevalent in people from Asia, Africa and Southern Europe; it decreases the further north and west you go. In Scandinavia only 3% of the population suffer from the condition, while this number rises to between 10% and 20% in Switzerland and Germany. So why do Europeans have fewer problems related to lactose? It is due to an interesting genetic mutation.

Genetic mutation at high velocity

It was assumed for a long time that lactose intolerance stemmed from the impact of migration to our continent from the Yamnaja culture, which originated in the Caucasian steppes. Our present genome provides clear evidence that our ancestors mixed with the local population of the time.

However, a research team from the University of Fribourg concluded that genetic mutation actually started around 1,000 years later. The evidence starts with the Battle of the Tollense Valley in northern Germany 3,000 years ago. Researchers were able to take DNA samples from 18 Tollense skeletons, 14 of which were usable and were examined at the university. The samples revealed something astonishing: of the 14 Tollense warriors, 13 could not process lactose.

From then on, it took about 120 generations before people could eat foods containing lactose without problems. In terms of evolutionary history, this was a rapid pace and a conflagration that spread over the whole of Central and Northern Europe 2,000 years later. The reasons are based on the Darwinian principle of natural selection.

Milk consumption based on natural selection

It can be assumed that famines, crop failures, pandemics and unclean water were very common in our latitudes.

It was a matter of life and death: those who could drink milk had a survival advantage.

If the fields withered and the reservoirs were empty or the water contaminated, the milk drinkers still had the cow. They were also less likely to suffer from typhus and cholera, which also impacted natural selection. Lactose-intolerant people were more likely to die before or during their reproductive years. The gene-mutated population grew faster and faster and prevailed in northern and Central Europe.

In the south, however, the food supply was more abundant, and the ability to drink milk was less crucial for life and death. This also partly explains the north-south divide in lactose intolerance.

Different lactose content of dairy products

Around 80% of the world’s population is lactose intolerant. They do not have to give up dairy products completely, because not every dairy product contains the same amount of lactose. The content depends on how it is processed and stored. While fresh milk that is barely processed still contains a lot of lactose, soft cheese only contains traces.

Hard cheese, on the other hand, is lactose-free. When cheese is made, most of the lactose is already excreted with the whey. The lactic acid bacteria break down the rest during the ripening process – cheese that can ripen for longer than six weeks is practically lactose-free.

HOCHDORF – the only Swiss provider of lactose-free milk powder

In response to the global issue of lactose intolerance, more and more products without lactose are coming onto the market.

Hochdorf can now offer its customers a wide range of lactose-free milk powders as ingredients for lactose-free yoghurts, desserts or other products – in the highest quality and made from the best Swiss milk. As well as supporting food manufacturers, end consumers who value delicious-tasting lactose-free products also benefit.

We will be happy to provide further information on our products.

Further information:

Sources:

1) Nmi Ernährung im Fokus / Laktoseintoleranz weltweite Verteilung (Nmi Nutrition in focus / Global distribution of lactose intolerance), Accessed 1 February 2023

2) Acroscope – Laktoseintoleranz (Acroscope – Lactose intolerance), Accessed 1 February 2023

3) Johannes Gutenberg Universität Mainz: "Lactose tolerance spread throughout Europe in only a few thousand years", Accessed 1 February 2023

3) universitas – The science magazine of the University of Fribourg: “Milchtrinken oder sterben” (Drink milk or die)"Accessed 1 February 2023

4) Joachim Burger, Daniel Wegmann et al.: "Low Prevalence of Lactase Persistence in Bronze Age Europe Indicates Ongoing Strong Selection over the Last 3,000 Years", Accessed 1 February 2023

5) Sge Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Ernährung: Publikation Ernährung bei Laktoseintoleranz (Milchzuckerverträglichkeit) (Nutrition for lactose intolerance (milk sugar tolerance) publication), Accessed 1 February 2023

Caption:

Lactose intolerance is widespread, but there is a strong north-south geographical divide in its frequency. (Source: NmiPortal - own creation / Food Intolerance Network, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Leave a comment